Uncategorized

Re-Discovering a New Lichen

What makes a ‘discovery’? Recently a lichen species was discovered, in a digitized collection of lichens that had already been collected and misidentified in the past. The digital databases for scientific collections of field samples allow researchers anywhere in the world to explore samples of lichens, and add new information learned since the time the specimen was collected.

https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/science/rare-lichen-unique-to-florida-may-be-extinct/

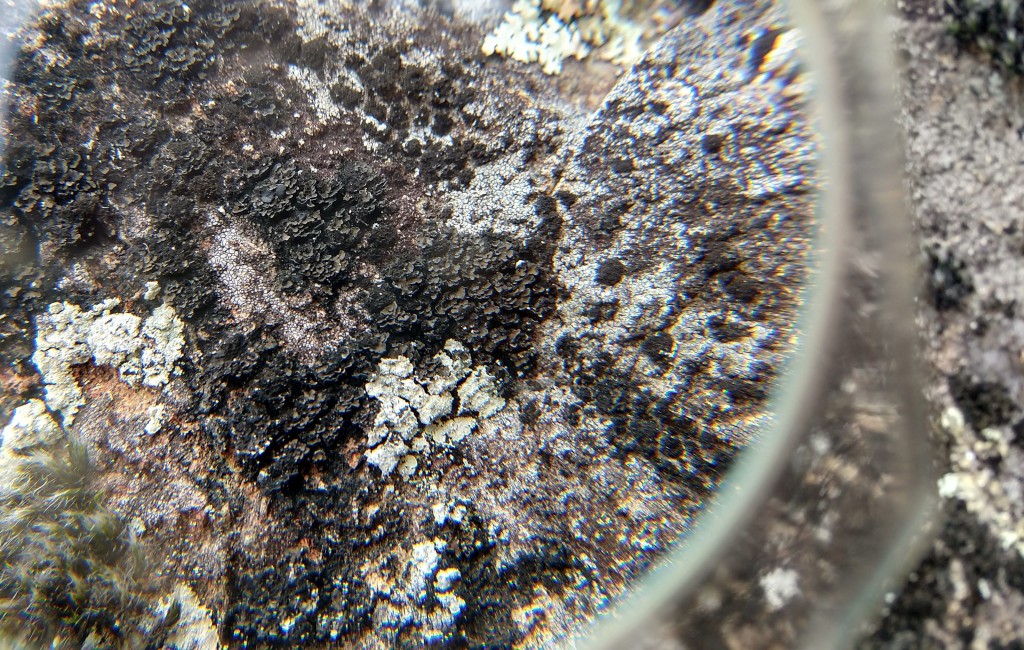

I apologize for not providing an image of the new lichen species; I can’t figure out how to manage some of the new aspects of this blog. However, the lichen image above is one of my ‘discoveries’. It is new to me; a discovery made on a slow mosey across a gravelly, cactus and creosote filled flat below Picacho Peak on a warm February evening. Finding a lichen I’ve never seen gives me all the good feelings of discovery; it matters not one tiny bit that others may have already looked at and identified this lichen.

The beautiful cactus above is about two inches tall, seen through a hand lens. This is the first rainbow hedgehog cactus I’ve found and it is a beauty. Unlike many of her kind, there are no pinkish bands of color, only the lace-like white net of spines. Accidentally finding this cactus while looking at lichens in a small rocky outcropping was the best moment of a day filled with excellent sightings and discoveries in a new place. I wonder how many other people wandering very close by on a well used trail have ever seen this tiny beautiful cactus. This was a discovery for me that feels very special.

The black lichen in the above image was a flat dark crust on the rock until I took a look through the hand lens. A multitude of tiny, leafy layers appeared, some with mahogany colors and some with pale edges. Neighbor to the hedgehog cactus, and part of the miniature garden that flourishes at the edge of a busy hiking trail, this lichen and so many others sharing the boulders scattered through the forest are easy to discover by anyone. Slow down, stop for a while and look around. Curiosity is the most effective ‘tool’ for discovering something new.

While idly wandering across gravel flats at Picacho Peak, wondering what might be on seemingly empty ground, I found not only several extremely tiny lichen colonies (see first image), but also found translucent, pale ants making mud tunnels the size of matchsticks, pack rat dens, bird nests, a butterfly new to me, and watched ravens play games with twigs on top of a saguaro. Lichens led me to everything else.

It doesn’t matter what interests you. Everything you find with curiosity becomes new. No matter how many times a familiar lichen is seen, or a bird sighted that you’ve come to overlook because they are so common, there is something new to learn. Discovery doesn’t only happen far away, on Mars or in a distant jungle, it happens in our own backyards and on our favorite walking trails.

I love lichens because their tiny size and inconspicuous ways encourage a slower, more careful observation. Noticing Lichen’s neighbors becomes easy, and before you know it, the forest or meadow is full of color and life you never noticed before. Discovery is not only finding what has never been known by humans, discovery occurs whenever we recognize something amazing or beautiful about the world around us. So next time you are out for a walk, be curious!

New Discovery in Lichen Partnerships

For some time lichenologists have known of two species of lichen that are made of the same algae and the same fungi partners, but appear very different. One has vulpinic acid, which makes the lichen bright yellow, the other is dark brown. Recently scientists began looking for more than one algae species in these lichens and found a mystery resident ; a basidiomycete yeast that lives in one species but not the other. Sorting through all the possible partners in a lichen seems daunting, but these scientists are up to the task. They hope to be able to induce lichen to form in vitro, so they can study up on some of their questions without collecting lichen from the wild. Did you know that lichen will not create themselves in an artificial environment? They know the difference.

Take a tour of beautiful lichen pictures while pondering whether those two lichens, one bright yellow and one brown, are really two separate species, and whether there could be more residents in any of those colorful Tiny Ones than we think, and whether they could be up to other behaviors and actions that we have no idea about yet.

It’s hard to believe that a living being that holds so still can be doing so much! Sequestering nitrogen from the air, absorbing poisons from our air pollution, making nutrients available to the trees they are attached to, making soil out of rocks, providing medicine for birds and animals in the form of antibiotics that the lichens make, insulating nests and dens, and much more. Lichen continue to quietly go about their work in the world, so slow down on your next walk in the woods, and look for the Tiny Ones on tree trunks and rocks. Put your ear down close to the ground or the bark and listen. Take a hand lens, and look closely. What’s going on?

Let me know what you find!

Lichens and CWD

I have good friends in Canada who are film makers, and currently they are making a documentary on Chronic Wasting Disease. Of course, Wisconsin was one of their destinations for filming, as well as western states, England and Norway. If you eat meat, or simply care about the health of wildlife, it is probably a good idea to pay attention to new information on this and similar diseases, as information is updated. One of the team members who has been working on CWD in Canada for many years told me about some research on lichens and prion disease . The Tiny Ones continue to amaze with yet another complex and very particular activity they perform, unknown to us. It may be very useful to us to learn how they deal with prions. This research is a start.

The researchers found three lichens that affected prions. One of them was Parmelia sulcata, pictured above with friends Moss and Flavopunctilia sp. The other two lichens were Lobaria pulmonaria and Cladonia rangiferina. I don’t think that Cladonia grows in this part of Wisconsin, but Lobaria pulmonaria does; sorry I don’t have an image for this post. Check Sharnoff’s lichen pages for images. These three lichens have a serine protease activity that breaks down the prion. The only way humans know how to break down a prion is with the use of extreme heat, high Ph levels and the use of detergents. There may be many ways that lichens can affect prions; the scientists are just getting started looking at how lichens do what they do. It probably is the fungal, mycobiont that is affecting the prion changes, but the researchers have many questions yet about how the lichens do what they do. We have talked about the many complexities of the lichens’ interactions with the environment, and unanswered questions we have, in other posts, so this isn’t new to Kickapoo Lichen Lovers!

Humans have just started looking at what the lichens are doing, and there are thousands of lichens, so it would be reasonable to suspect other species may have similar abilities.

I love to think about why certain lichens would find it useful to de-activate prions. What interactions might occur in their part of the world, that causes a lichen to even notice a prion? Could a prion harm lichens? Does a prion interfere with photosynthesis, or other functions of the photobiont or mycobiont partners? Maybe the mycobiont is simply ‘hunting’….just to bag that rare prion. (It’s ok to laugh….)

We have known for a long time that lichens have many antibiotic properties; maybe half the lichen species humans have checked have some antibiotic function. Birds line nests with known antibiotic-making lichens, which may keep nestlings safer from disease. We know lichens can detoxify pollutants they extract from the air. Maybe one of their functions in the world is to clean things up.

We will never know all the reasons, or all that any plant or animal does with its life that is useful and necessary for the other plants, animals, microbes, insects, and everyone else in the Web of Life. Learning even a small part of what’s going on around us opens us up to wonder, and sparks interest and then, with any luck for all the other life on earth, we are motivated to take care, and do less harm. The news that my special friends the Lichens are already dealing with prions made me laugh. Of course! They have been here millions of years longer than us, and have had a long time to develop elegant responses to the world around them. May we be able to follow their example.

acrylic on panel

Foreign Lichens

My friend Peter Schmidt was visiting Germany recently and found this tree branch in a woodland area. He thoughtfully shared it with your local Lichen Hunter. I have no idea what it is, but am going to spend some time with my lichen resources to challenge myself.

On the left there are some distant branches with yellow lichen; a careful look around this woodland might find more interesting species in addition to these bright yellow ones.

Here’s a closer view. Although the resolution is not good enlarged, we can see it is a foliose type of lichen; it has some leafy growth in areas and looks wrinkled, as if it is not tightly attached to the branch, as a crustose lichen would be.

Last summer I posted images from British Columbia, Canada, of the yellow lichens that are very common there in the fir and spruce forests.

The Letharia is a fruticose type lichen; it has branches, grows upright or trailing and is attached to the tree at small, discrete spots, just like a shrub growing in the ground.

Letharia vulpina uses vulpinic acid to make the yellow color, which is poisonous. In some parts of the north it has been used as a poison to kill wolves and other animals. It is toxic to any meat-eating mammal, as well as to molluscs and insects. But it does not affect mice and rabbits! The lichens use vulpinic acid to control the amount of light absorbed. (Lichen Biology, Thomas H. Nash III). The German lichen may use a different chemical to make its yellow color; a mystery I won’t solve today.

This spring I’ll go out looking for yellow colored lichens in the Kickapoo Valley Reserve and Wildcat Mountain State Park. Join me! No matter what we find, we’ll have a good walk in the woods.

Remember, look for the Tiny Ones when you are out walking.

Susan

Winter Lichen Hunting Memories

It’s raining tonight (February 23rd) and quite unpleasant outside. Today I retrieved from a drawer the lichen samples I collected last summer in Canada, with the intention of finally identifying the species. While traveling I discovered that the plastic clam boxes that fruit is sold in make great traveling sample containers for all sorts of delicate pieces of lichen as well as shells, bark, fallen birds’ eggs and dead bugs. I like to bring home all those things, look at them for a while then return them to the woods and fields to keep their place in the cycle of life.

Often, in many places, the only way berries and other small produce is sold is in plastic clamshell boxes, so I ended up with a few of them during our travels. I don’t buy food in plastic containers, but made a temporary exception during a few days of the trip. The paper envelopes usually used to hold lichen samples work the best, and they too can rejoin the circle of life when we are done using them. So now I’m sorting out the lichens from their plastic cages, and enjoying the memories of finding them during the summer’s travels.

The Peltigera in British Columbia can also be found here in Wisconsin. When walking the KVR Wintergreen Bluff Trail stop at Lichen Site 4 (the rocky flat area) and look carefully for this species. There is quite a large area of them. Please stay on the trail while looking, so you don’t crush the Tiny Ones! At different times and weathers, these lichens will change dramatically, from being almost invisible to looking like they do in this picture.

Here’s what the bench land looks like above the Columbia River in southeast British Columbia. This is a Nature Conservancy area so has been protected from excessive damage. Much of the bench lands are built on, and the lichens are few in those places.

Walking the trails here, this is what the ground looks like:

While walking, and especially biking through here, looking out at the scenery or the next obstacle to maneuver around, the life on the ground is something no one notices. Yet this microbiome is holding all the larger life in place, creating and protecting an environment, shelter, food supply system, promoting health, preventing erosion and more. As it disappears when we travel over it or dig it up, the diversity and therefore the sustainability of the whole area fails.

When we step on the ground here, it sounds a bit crunchy, and it is; the dry lichens break off and the delicate crust on the surface of the ground is broken open. All dry, open soils naturally have some microbiome crust, unless disturbed. This allows dry grasslands and even deserts to support a tremendous variety and number of living beings, from plants to insects, birds, mammals, reptiles and even humans.

These dry grassy areas in the western areas of our continent should be covered in some form of this microbiome. When visiting these areas, go slowly and look at what is on the soil and rocks, then step carefully. There is a miniature world at your feet as complex as the world of trees, grass and animals we are familiar with.

Leaving the dry grasslands and moving into the more tree covered slopes of the lower mountain elevations, there continues to be much life on the soil and rocks, but the trees also support a vast community of lichens. From deep rainforest communities to dry open pine forest, lichens love it here.

The colors and shapes rival any garden. Each time a new rock is found, the lichen shapes and colors are different. Trees are festooned with bright yellow, pale yellow and greens of Usnea and Vulpicida as well as the grays and greens and blacks of Letharia, Hypogemnias and more.

Yes, I do get those seed catalogs, and can get lost dreaming in them on winter days, but an excellent variation of that pastime is looking at lichen pictures. If there are not enough pictures here for you, try the best lichen picture site ever -Stephen Sharnoff’s amazing website. Add some color and amazement to your gray winter days by sharing this lichen blog and Sharnoff’s site too, with others, especially kids!

Contact us at the Kickapoo Valley Reserve if you want help learning about lichens. Come out and walk the Lichen Trail. Even in winter you’ll find some color and intrigue in Lichen Land. Thanks for reading this blog. Please share with others, to spread the news about our friends in Lichen Land.

Lichen Poetry

Poetry and lichens are two inspirations for me. I wrote a little lichen poem:

I’m liken’ lichens

they’re lookin’ lovely,

Like little lilies

all lined up on a log.

Of course it’s not very ‘good’! But it is fun. Lichens often seem very cheerful and playful. Any time there are so many shapes and colors, there has to be a party going on. I think it is the party of Life happening!

Greater poets than I have also noticed lichens, and each poet has a unique perspective. Pablo Neruda is one of my favorite poets. Here is his poem about lichens.

Lichen on Stone by Pablo Neruda

Lichen on stone: the web

of green rubber

weaves an old hieroglyphic,

unfolding the script

of the sea

on the curve of a boulder.

The sun reads it. The mollusk devours it.

Fish slither on stone,

with a bristling of hackles.

An alphabet moves in the silence,

printing its drowned incunabula

on the naked flank of the beaches.

The lichens

climb, higher, plaiting and braiding,

piling their nap in the caverns of

the ocean and air, coming and going,

until nothing may dance but the wave

and nothing persist but the wind.

If you are not familiar with Neruda’s work, read his Ode to Socks, and you will have a new love for a good pair of socks. Speaking of socks, I would love to have a nice warm pair of winter socks, with lichens crocheted or knitted around the top. It would go splendidly with my Lichen Hat. But my knitting skills are a long way from accomplishing those socks. Speaking of warm socks, now that it’s colder, and here in the Kickapoo, mostly damp and wet, it’s a good time to check your favorite rock or tree trunk for lichen activity. Of course, you won’t actually see any movement, but this is where memory is an important part of learning. Remember the last time you looked at that tree or rock?

These two images of lichen covered rock are not exactly the same place, but illustrate the differences that can occur between wet and dry conditions. What is inconspicuous one day will be illuminated with color another day. Winter is a great time to see lichens, as the leaves that often cover them are gone. If there is not much snow the lichens are very visible, and of course on trees they are always visible.

If you see a beautiful lichen (use your hand lens!) and are inspired to write a poem, or just want to describe and complement the lichen, send your comment to this blog. If you give your name, I’ll send you a hand lens! Anonymous is ok too. Poems can be any length, any style, any degree of expertise; new poets are especially encouraged (I am one too). There will be a visit to the lichens, to read the poems to them, and anyone can come along for Lichen Hiking. Thanks for sharing this blog, and spreading Lichen Love!

Lichens and Fires

Wildfire effects on lichens have recently been coming to the attention of biologists and foresters who are studying the long term effects of the very hot fires that have become more common in the North American west. The forests developed over thousands of years to withstand and benefit from low intensity, frequent fires. We humans suppressed the fires for over 100 years, and now the increasing but historically normal dry conditions and build up of unburned woody material in the forests, as well as the vast number of beetle-killed trees create conditions that encourage fires to start and burn hotter than normal.

These super hot fires burn the forest more completely, killing all the lichens. Many years later there are no signs of lichens in the burned areas. Scientists suspect the lichens will not return until the forests grow large, older trees that provide habitat for lichens. The lack of lichens in a new forest will affect the health of the trees, and the ability of many animals and insects and birds to live in a burned over area. Many species depend on lichens for some aspect of their lives; without lichens, these residents disappear.

When we see the diversity and quantity of lichens in an established forest, it becomes clear they are an important part of the community. After a fire, and also after human logging activity forests do regrow, but we are only starting to understand some of the ways each member of the forest plays an essential role in making a resilient, vibrant, and sustainable environment that all life can depend on. We are starting to realize that some trees and other plants growing after a fire are only a small part of the life that needs to become established and begin cooperating to make a real forest. Maybe in the future we will change our management habits to not suppress natural processes, and when we do interfere, we will use more comprehensive methods to renew the forest, such as inoculate with lichen spores as we plant trees, consider helping other plants grow, and diversify the species we plant. We’ll also need to choose trees, forbes, lichens and maybe even soil microbes that fit the environment being addressed.

We’ll need to think about the combinations and timing of introducing species. Just sticking some pine trees into the ground is not in any sense ‘reforestation’. (I planted trees for paper companies for years and was rudely awakened by what passed for ‘reforestation’.)

While we contemplate these ideas, we also have to learn at what stage of a forest’s growth each member of the community enters and establishes itself. We know in general, but I am sure we have a lot to learn. We know lichens are one of the first to colonize new earth, then moss, liverworts, ferns and on to larger plants. Each species, each facet of rock, wood or soil has special properties; they combine and change in minute but critical ways, in an elaborate dance with each other.

Maybe one of the good things to come out of the tragic fires in the western forests will be a desire to regrow forests that are resilient and adaptable as well as useful for our timber needs.

NOTE: Identification of lichens in these photos is tentative. If anyone reading this site has a suggestion for a more accurate identification, please contact me. Thanks!

Party Time in Lichen Land!

Here in Lichen Land, the tiny but vast community of lichens, bryophytes and fungi are having a party on the Wintergreen Trail. Cladonia and Peltigera, Stereocaulon and Candelariella, Xanthoparmelia and a small crowd of their crustose friends are sporting fancy apothecia (disc or cup that produces spores) in many shapes and colors. The place is decorated in the brightest colors-turquoise, jade green, yellow, white, black, gray, brown, rust, pale blue. A Cladonia first caught my eye; she was fringed and spangled with intricate weavings of pale green, crowned with a russet apothecia/cap perched on her tall slender podetia (stalk). Many other Cladonias waved jade colored cups, some fringed and some smooth edged. The Peltigera rufescens, that not long ago sported velvety gray thallus and dramatic, hooded, vase-like apothecia, now were a bit faded in places. But some of them had grown dozens of tiny, white rhizines (root like structures) from the underside of the thallus (the vegetative part of a lichen that contains the photobiant and mycobiont.

All this elaborate activity goes on within one inch of the ground. A wrong step by a human would destroy many years of growth. But you can join the party; pack a 6x or 10x hand lens, your camera, and just walk into Lichen Site 4. They’ll all be there. Once you step down the two stone steps and turn right, slow down. Stop. Take out the hand lens. Breathe and relax. Even though it’s a party down there, we need to slow down to join up with the Tiny Ones.

Have you ever hunted for 4-leaf clovers? Use the same type of gaze and attitude; you’ll be more successful with lichens because there are so many of them, you can’t miss them. Once a few are seen on the pine needle covered ground you will start to see the stalk-like podetia everywhere. Get down close to them, use your hand lens held close to your eye, then move closer or farther from the lichen to focus, keeping the lens close to your eye.

At ground level the elaborate, fringed structures make a fairyland scene. A few weeks ago, the podetia were straight and smooth pointed stalks. Now they sport cups, caps and fringes. The thallus (the leafy part) may have rhizines, brighter color and also more elaborate shapes. There are many very tiny lichen growing among the taller ones so be careful where you step! It truly is a forest in miniature, with a canopy, mid layer and ground layer of plants and animals.

There are several types and species of lichen sharing Cladonia’s forest. Peltigera sp. has been introduced earlier, but there are many more lichen here. On the edge of the narrow pathway, rocks with lichens barely discernible in the summer now are alive with color and texture. These are crustose lichens, and there are quite a few species here. Many

species of crustose lichen on the rocks at this site have produced apothecia. Look for dark spots in the light colored crustose lichen body. Most of the lichen on these rocks are white, gray, or blue-gray. There also are some black crustose lichen here. Look closely with your hand lens to check for apothecia on the black lichen; they are hard to see. How many different species of lichen can you find? These can be very hard to identify without a high powered microscope to see details, and chemicals to test certain reactions lichens may have. At this time, the Lichen Hunters are simply recognizing these are ‘crustose’ forms.

On the low, sandy cliff (the cliff is 2-3 feet high) at the top of this area, the walls have been decorated in turquoise, green and white. The colors are bright and clear. In the shadows under the rocky overhang, the gauzy, lacy texture of lichen mixed with moss, spider webs and falling grains of sand make a confusing scene. What is lichen, and what is sand grains, or spider webs?

As the sunbeams illuminated strands of turquoise and green against the dark recesses it seemed to be an endless mass of tangled threads. Much of the lichen here is probably a Stereocaulon sp. commonly called ‘Rock Foam’. There are several species, some of which, in the arctic, are food for caribou during famine.

Pixie Foam, a miniature Stereocaulon species, often grows where there is a high concentration of metals in the rock. Lichens are used all over the world to prospect for minerals by analyzing the mineral content of the lichen thallus. (From ‘Lichens of the North Woods).

How many species of lichens can you sort out, under the sandy ledge? There are also mosses, ferns and fungi here. How many different life forms can you find, of any kind? This is a rich, active place, yet we know almost nothing about the lives here, or what their place in the world might be.

This visit to Lichen Land left me feeling as if I’d crashed a party. The last time I was here, the lichen were growing podetia but were much smaller. Today I crossed the threshold of two stone steps into their world, and it had changed dramatically. Colors were brilliant, forms were elaborate; the lichens seemed more alive! They didn’t seem like the same lichens I’d seen earlier. It was quiet, but I felt there was music and shouting and dancing going on, in a tiny way. It felt like a party.

As I walked away I thought about how the earth, rock, sand, and trees, each have a community of lichen. They are not plants, they are not animals; they are simply something else. What do they weave for the web of life in the world as we know it? Why do they cover such a large part of the earth’s land surface? There are over a hundred species of lichens on the base of the trees in the Kickapoo Valley Reserve. We don’t know how many different ones are in the canopy, or the soil or on the rocks here. Everything in Nature has a place and a purpose. The Lichen Hunters are exploring what that might be for the lichens in the Kickapoo. Come on out for a walk in the woods and help us learn about the Tiny Ones.

Building with Lichens

Did you know that many, maybe most lichens have some antibiotic properties? Animals and birds know this and eat or use lichens in various ways that may help them stay healthy. One common use of lichens is as a construction material in bird nests. The lichens may help keep baby birds disease free. Many birds use lichens, so look for nests especially when the leaves fall off the trees in autumn and nests are easier to find, and notice how many may have some lichens incorporated. If you can figure out what species of bird made the nest, that’s even better. Please let the Lichen Hunters know of your find.

It is not for us to know all the reasons a blue -gray gnatcatcher builds its home with lichens, but I can think of several possible reasons. Of course one reason is the known antibiotic property of the lichen; a built in disinfectant, in the walls of this perfect little home! Another reason may be that lichens are beautiful; the lovely blue-gray color the gnatcatcher likes in the lichens can be found in elegant home decor magazines, for human homes. Maybe the blue-gray gnatcatcher is matching its own color by using the same color of lichen on its nest walls, as we would wear harmonious colors because they are pleasing to see. Another reason may be that the flat surface of the foliose lichen may be somewhat water resistant and makes a nice solid surface. Also, since the lichens grow on the tree branches, covering the nest with the same lichen is good camouflage, hiding the chicks who would be a tasty treat for many predators, as well as the adult birds when they are resting on the nest.

Years ago I found a hummingbird nest made of lichens, in an apple tree. The nest was the size of a thimble. I considered it a small miracle that branch appeared right in front of me while picking apples.

This lovely photograph is from Paul and Bernadette Hayes. They recently found the nest about 10 feet up in a box elder tree, on a horizontal branch. It is the home of a bluegray gnatcatcher. Thank you Paul and Bernadette.

Discovering a well made birds nest covered in lichen is a lucky find. Please share your discoveries so we can learn about the birds in our home territory that use lichens.

Winter Lichens

Today a friend and I walked to the top of Black Hawk rock. A light snow still covered shady areas, the sun was low in the sky and gray-blue clouds scattered into the distance. There was no wind, no birds singing. A flock of turkeys walked across the ridge above us making clucky noises. As we climbed up the west side of the hill, the colors of tree trunks, fallen leaves, and rocks seemed to get brighter and brighter. Greens, blues, white, yellow. Lichens! If they could sing, they probably would be doing a hallelujah chorus today. Everything is saturated from many days of rain and light snow, and the temperatures have been above or near freezing, and nothing else is growing to block the light. The Little Ones are feeling good! The forest is full of living, growing plants in the middle of winter. They are all very tiny and all they need is moisture, light and above freezing temperatures to flourish while all other plants and most animals are dormant.

Green and blue lichen covered pieces of bark scattered on the ground from a fallen branch.

Part way up the hill a tree trunk was lined with white stripes. From smooth white layers to toothed patches this fungus (possibly Irpex lacteus) changed shape and finally supported small white fungus with purple red undersides.

Moss, liverworts and lichens crowded branches and then rocks as we climbed onto the top of the ridge.

At the top we stand on the rocky point and the whole Kickapoo valley falls away into the distance; to the east, south and west. The sun breaks through clouds illuminating the far reaches of the valley and fallow fields turned golden. Juniper and oak cling to bare rock here and the lichen cling to the trees and rock. Every living thing is attached to another living thing. Snow and lichen share the rough branches. Some of the lichen are frozen solid but close to them others are soft and flexible. The cup shaped lichen are frozen solid, the liverworts, moss and flat green lichen are not, in the picture below.

The rock at the top of the cliff feels many footsteps over time but lichen are everywhere here. Gray, yellow, orange, blue, green, purple, white; the rock looks painted with lichens. We look down across the valley and realize that much of the color we see in the landscape is the color of the lichen and mosses that are an essential part of the system of lives that make our world alive. The white and pale green colors of branches in the treetops are lichen; the yellow, gold, green and black of rock faces are lichens, and their companions the moss and liverworts.

We ended the day walking through a field of big bluestem and other prairie plants, now golden and coppery in the sun. We know tomorrow the Little Ones will be frozen and dormant under the coming snowstorm; but as soon as the sun touches them again they will come back to life.

PS: My attempts to name species is open for corrections and suggestions. We are working on learning to identify lichen (and fungi and moss) so at this time are making guesses at best. If you know what a lichen or plant is in one of these pictures, please let us know what you think.

Susan